Community Methods

The Relational Method

“The best research is produced when researchers and communities work together”

— Nature Editors (2018): World’s leading multidisciplinary science journal

Community Methods Pages:

Amanda Tattersall and Marc Stears have developed a particular approach to community methods called the relational method, which adapts the civil society practice known as community organising into a research method. The US tradition of community organising practiced by the Industrial Areas Foundation amongst others had its roots in the work of Saul Alinsky in 1930s Chicago. But before Alinsky built the Back of the Years Neighbhourhood Council he was a PhD dropout from Chicago’s School of Sociology. At the Chicago School Alinsky studied under Robert Park and Ernest Park alongside other innovative urban ethnographers, learning many of the principles and practices that Alinksy later adapted into community organising. Tattersall and Stears argue that these early methodological innovations make community organising well suited as a community research method, with organising not only emerging out of scholarly research practice but having been refined and improved by civil society over the past 80 years.

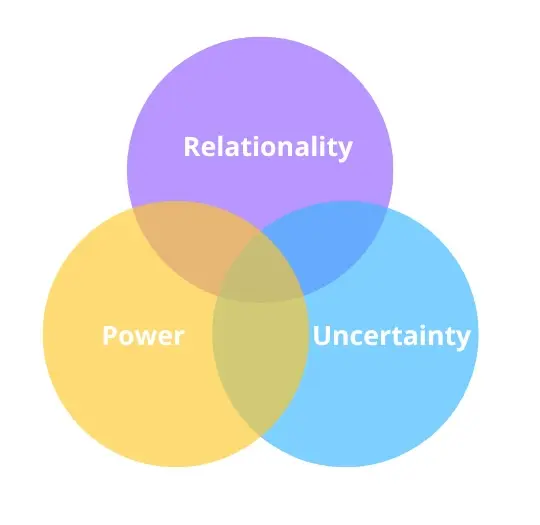

The relational method is anchored in three key elements – relationality, power and uncertainty – and they unpack the foundations and core considerations for researchers and policy makers in how to undertake community methods. Relationality refers to the importance of deep relationship building preceding research gathering and data collection. It speaks to the power of building strong one-to-one relationships between researchers and community participants, and the tool of the relational meeting as a way of doing this. Relationality brings with it a pedagogy that informs powerful public interactions, including concepts like public and private, self-interest and most importantly power. Power stresses that everything in public life, including the researcher-community relationship, operates in a dynamic of power. It calls for a sophisticated approach to research engagement and impact, and uses the tool of the power analysis to identify community participants and stakeholders. Finally the concept of uncertainty recognises that all knowledge is contingent and incomplete, despite the confidence of university rankings and journal citations. It makes an argument for seeing research like public life more broadly, as a process of constant iteration and discovery.

The relational method is briefly outlined here, and its history described here, with a comprehensive peer-reviewed survey of the relational method outlined in an upcoming peer-reviewed article. A selection of resources for researchers are included below, and for more information and inquiries about workshops and training on these methods go to the website’s contact section.